Let’s face it—sometimes writing can be hard work. For example, you may not really care about Russia’s GDP in 1933 (or, then, perhaps you might). Likewise, the migration habits of squid are not at the top of most students’ lists of captivating studies. Nevertheless, to get a good grade (and to learn something, of course), it is necessary at times to do a good job and write a solid paper.

Here are some helpful tips to writing those “ugh” papers (and any other papers, for that matter).

Choose to have a good attitude:

If you look at it as a learning experience (which it is, not only in your subject matter, but also as an exercise in self-discipline, writing, and probably research), you can really motivate yourself to get something out of this.

Fact is, some of the most personally rewarding papers you write may not be the ones you’re naturally motivated to write. On the contrary, the ones that you have to stir yourself up to do will be the ones that make you feel really good when you end up with a good grade.

Basically, before you even start doing the actual work, you need to tell yourself that you can do this paper; you can do a good job on this paper; and you will both learn from it and feel great when you accomplish this task that is not naturally appealing. And during the times you feel like, “Why do I have to do this stupid assignment?” just remember the preceding points.

Make a plan:

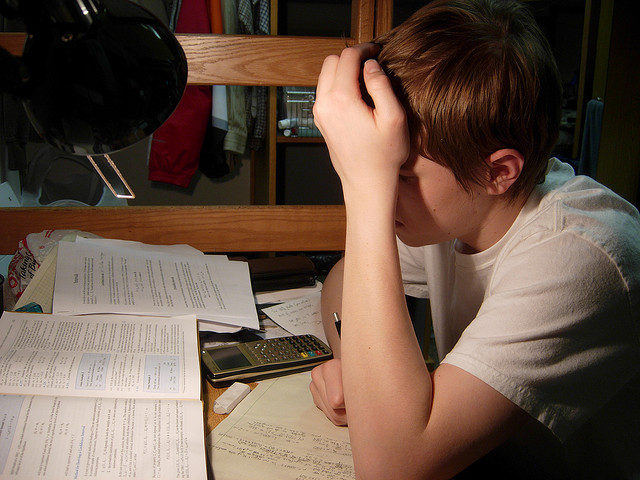

When you’re intrinsically motivated to do a paper, it comes easy. Even then, however, you should be as organized as possible. But when the subject matter is something you don’t really care about, you have to protect yourself from the natural tendencies to escape from applying yourself to the task at hand.

With this in mind, insulate yourself from TV, friends, other work, or anything else that would give you an excuse to stop doing what you need to do to succeed at this writing. Keep in mind, however, that it is especially important to reward yourself with breaks periodically, or you can get burned out and really frustrated.

Make the most of unappealing writing assignments. The ones you enjoy will come along soon enough.