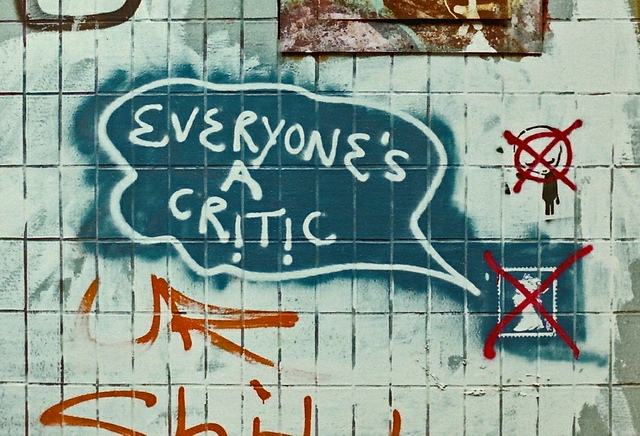

Many of us have heard of stage fright, and most of us have experienced it, too. What about page fright, though? It’s that sickening feeling you get in the pit of your stomach when you face a pristine piece of paper or a blank computer screen. And one big source of a writer’s nervousness and nausea is that troll of a critic that resides in all of our heads, even those of the most experienced writers. Mine might look and sound different from yours – they often take on the persona and voice of a particularly mean English teacher who once tortured us – but the critics all yammer on about the same kinds of things. They say, “What makes you think you can write? You can’t spell. You can’t tell a comma from a piece of cheddar cheese. No one’s going to want to read what you have to say.” So how do you get Ms. McGillicutty or Professor Burnbottom to shut up?

The best way to silence the critic is to put something, anything on the page. The nice thing about writing, as opposed to talking, is that it can be edited until you have it just right. So just set a kitchen timer for five or ten minutes, and until the little bell dings, just dump everything you can think of about your subject on the page. This is called free writing, one of the early steps in the writing process. Now you no longer have a blank page, and some of those butterflies in your stomach have probably taken off. You probably aren’t hearing much from that critic, either, because your mind has been on getting your ideas down as fast as you can.

Now read over what you’ve poured onto the page and start cutting and pasting, adding to, and rearranging your ideas until a pattern starts to form. You’re still in the early stage of writing, so don’t worry about spelling and grammar and punctuation at this point. Just concentrate on getting your ideas down and playing around with them. You can worry about the formal mechanics of writing in a much later stage. The most important thing you need to do as a writer is have something important you want to communicate and work on finding the best words and details to make those ideas come alive and be meaningful for your readers.