Okay, so you’ve got a paper due in a week. Will you get it done on time? Sure! Well, I think so. I mean, maybe, if I don’t get too caught up with other stuff. Um, actually, I don’t know, but hopefully I can pull it off.

If you’ve ever been in a position like this, you may realize the importance of being organized. In fairness, this is something that most of us struggle with. However, deadlines are deadlines, whether you’re a student or an employee. Here are some tips to help you make sure you don’t miss the deadline for your next essay.

Consult your syllabus:

Most syllabi will tell you when important papers are due, and how long they should be. You may want to ask the teacher how much preparation time will be needed. Then you can plan for this project weeks in advance, setting aside time to get it done.

Start immediately:

This doesn’t mean to necessarily start writing or researching immediately. Rather, it means that as soon as you are assigned the paper, you adjust your schedule and plans right away to accommodate it.

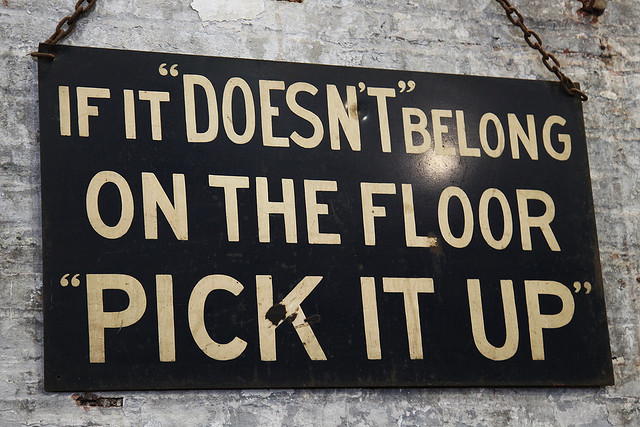

Prioritize:

Since you probably have several classes (and some kind of a life, job, relationships, etc.), you can’t just shut out everything all the time. By putting things in their proper place, however, you can be sure to have a good plan that will work, and will enable you to meet your obligations while still enjoying life.

Be careful not to get sidetracked:

Yeah, I’ve got this paper due, but I don’t want to miss Gilligan’s Island tonight. It’s that one real cool episode with…Come on. You can find a million reasons not to do the work, but when it actually comes due, you’re going to want to have it done. And getting it done doesn’t happen by accident. Stay focused.

Reward yourself as appropriate:

If you stick to your schedule of working three hours on your paper tonight, you deserve a treat! Let yourself have fun. Give yourself positive reinforcement for doing the right thing.

So, be organized, enjoy yourself, and good luck on your next essay!